What hidden danger could cause a steel structure to fail without warning? Hydrogen-induced cracking (HIC) is a critical issue affecting many industries, where hydrogen atoms infiltrate steel, leading to embrittlement and eventual fracture. This article explores the causes, mechanisms, and prevention methods for HIC, helping you understand the necessary steps to protect your steel components from this silent threat. Learn how to identify the risk factors and implement effective solutions to maintain the integrity of your structures.

Hydrogen is known to cause embrittlement and cracking in steel, commonly referred to as hydrogen-induced cracking (HIC). HIC typically occurs in aqueous solutions, as hydrogen can diffuse into the steel matrix, resulting in steel embrittlement and cracking.

HIC is primarily discussed today, as it is a major concern in many industries. It is often caused by accidental factors during the forming or finishing process that allow hydrogen to enter the steel matrix.

HIC is influenced by three primary factors: material performance, environmental conditions, and stress.

Bubbling on the sample surface after hydrogen charging

During the Second World War, an RAF Spitfire fighter fell from the air due to mechanical failure, killing the pilot instantly. The incident was considered of great importance, prompting the authorities to collect all parts of the plane and establish a special investigation team to determine the cause of the crash.

The investigation revealed that the aircraft crash was caused by the fracture of the main shaft. The fracture showed multiple small cracks, known at the time as hairline fractures.

In 1940, Mr. Li Xun, the founder of the Institute of Metal Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, began research work at the University of Sheffield after graduating. The prerequisite for solving this problem was to find a way to quantitatively test and analyze the hydrogen content in steel.

Subsequently, Mr. Li Xun invented a hydrogen determinator to measure the hydrogen content in steel. It was eventually proven that hydrogen was responsible for the fracture of the aircraft’s main shaft. As a result, Mr. Li Xun became the founder of the field of hydrogen-induced cracking.

High-strength steels containing chromium and nickel are highly susceptible to hydrogen. Steels with high carbon content have a greater tendency to hydrogen-induced cracking, while low carbon steels are less prone to this phenomenon.

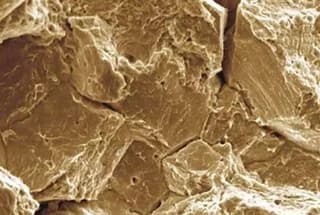

Forgings with a dense structure are more susceptible to hydrogen-induced cracking than castings with a loose structure. When hydrogen atoms penetrate into the steel, the atomic bonding force between grains decreases, and the steel’s toughness is compromised. The fracture caused by hydrogen-induced cracking is similar to other brittle fractures, and high-strength materials are more susceptible to intergranular fracture.

In low carbon steel, small and incomplete dimples are likely to appear on the small facets along the grain, forming what is known as the “chicken claw pattern.”

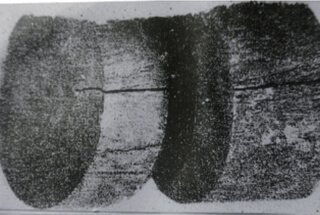

Hydrogen embrittlement fracture

Hydrogen induced cracking has hysteresis.

The occurrence of hydrogen-induced cracking in welded components can be sudden and poses a serious threat to both people and property. This issue demands great attention.

Explosion accident

The elimination of hydrogen in metals is a critical issue that requires attention. Certain steels or components used under specific conditions must undergo dehydrogenation treatment. For instance, galvanized parts used in aircraft must undergo this process. Hydrogen removal is also necessary for zinc plating on elastic parts and high-strength steel.

The process of removing hydrogen from parts involves heating treatment. The effectiveness of hydrogen removal is dependent on the hydrogen removal temperature and holding time. The higher the temperature and the longer the time, the more effective the hydrogen removal will be.

Typically, the component to be treated can be placed in a vacuum oven and treated at a temperature of 200-250°C for 2-3 hours. Hot oil can also be used to achieve the same hydrogen removal effect as the oven. This method offers the benefit of uniform heating and simpler equipment requirements.