Imagine welding metal with a beam of light—precise, fast, and almost magical. This is laser welding, a technology revolutionizing manufacturing. In this article, we’ll explore the fundamental principles of laser welding, its types, and its advantages over traditional methods. By the end, you’ll understand how laser welding can enhance production efficiency and quality in various industries. Ready to dive into the future of welding?

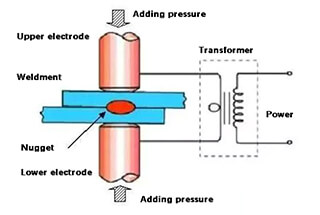

Laser welding is an advanced joining process that utilizes a highly focused, high-intensity laser beam to fuse metal surfaces. The process begins when the concentrated laser energy is directed onto the workpiece, typically through precision optics. As the laser interacts with the metal, it rapidly heats the material to its melting point through a combination of photon absorption and heat conduction.

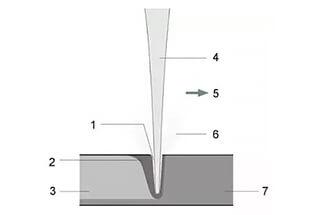

The intense, localized heat creates a keyhole-shaped weld pool, characterized by a narrow, deep penetration profile. This keyhole effect allows for efficient energy coupling and enables single-pass welds in thicker materials. As the laser beam moves along the joint line, the molten metal at the leading edge of the weld pool flows around the keyhole and solidifies at the trailing edge, forming a continuous weld seam.

The process is typically performed in a controlled atmosphere, often using shielding gases like argon or helium to protect the weld pool from oxidation and improve beam coupling. Advanced laser welding systems may incorporate real-time monitoring and adaptive control to ensure consistent weld quality and penetration depth.

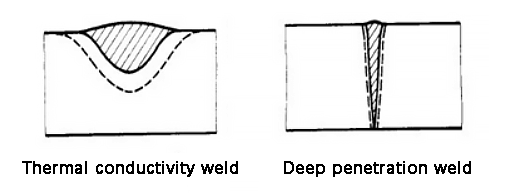

There are two mechanisms of laser welding:

1. Heat conduction welding:

When a laser is directed onto a material surface, some of the laser energy is reflected while the rest is absorbed by the material. This absorbed energy is converted into heat, which causes the material to heat up and melt.

The heat from the surface layer of the material continues to transfer through heat conduction to the deeper layers of the material until the two pieces being welded are joined together.

Pulse laser welding machines are commonly used for this process, and the depth-to-width ratio is typically less than 1.

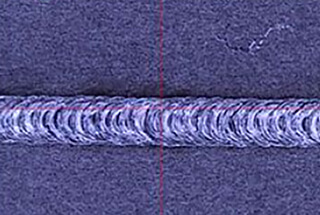

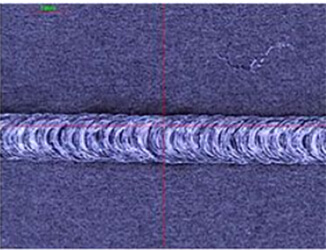

Drawing pipe welding – continuous welding

2. Laser deep penetration welding

When a high-power density laser beam is directed onto a material surface, the material absorbs the light energy and converts it into heat energy. As a result, the material heats up, melts, and vaporizes, producing a large amount of metal vapor.

The reaction force from the exiting vapor pushes the molten metal around, creating pits. With continuous laser irradiation, the pits penetrate deeper into the material.

When the laser is turned off, the molten metal around the pits flows back and solidifies, resulting in the two pieces being welded together.

This process is commonly used in continuous laser welding machines, and the depth-to-width ratio is typically greater than 1.

Laser welding is distinguished by its exceptional speed, profound penetration depth, and minimal heat-affected zone, resulting in negligible distortion of the welded materials. This precision makes it ideal for applications requiring high accuracy and structural integrity.

The versatility of laser welding is evident in its ability to operate across diverse environments. It can be performed at ambient temperatures or under controlled atmospheric conditions, with relatively simple equipment setups. The laser beam’s immunity to electromagnetic interference allows for consistent performance in various industrial settings. Notably, laser welding can be executed in vacuum, air, or specific gas environments, and even through transparent materials like glass, opening up unique fabrication possibilities.

One of laser welding’s most significant advantages is its capacity to join dissimilar and refractory materials. It excels in welding high-melting-point metals such as titanium and ceramics like quartz, achieving superior joint quality where traditional welding methods often fail. This capability is particularly valuable in aerospace and advanced manufacturing sectors.

Modern high-power laser welding systems can achieve remarkable power densities, resulting in weld depth-to-width ratios of up to 5:1 or greater. This high aspect ratio enables deep penetration welds with minimal heat input, crucial for maintaining the mechanical properties of heat-sensitive materials.

The precision of laser welding extends to micro-scale applications. By focusing the beam to an extremely small spot size (often less than 100 μm) with high positional accuracy, laser welding facilitates the assembly of miniature components and microelectronic devices. This micro-welding capability is indispensable in industries such as medical device manufacturing and semiconductor production.

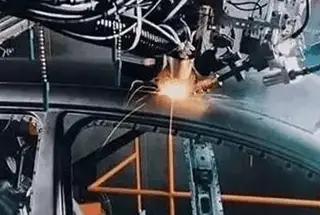

Laser welding’s non-contact nature allows for remote welding operations, accessing hard-to-reach areas in complex assemblies. This feature, combined with robotic integration, provides unparalleled flexibility in production line design and automation strategies.

Advanced laser systems offer beam splitting capabilities, both in terms of energy distribution and time-sharing. This enables multi-station simultaneous welding or time-division multiplexing of a single laser source across multiple workstations. Such configurations significantly enhance production throughput and equipment utilization, making laser welding a cost-effective solution for high-volume manufacturing scenarios.

Furthermore, the precise control over energy input in laser welding allows for tailored thermal cycles, critical for maintaining desired microstructures in advanced alloys and reducing residual stresses in welded components. This level of process control contributes to improved fatigue resistance and overall joint performance in demanding applications.

There are two types of laser welding: pulse laser welding and fiber continuous laser welding, which are classified based on the type of laser used.

Here are the differences between the two methods:

Continuous welding pattern

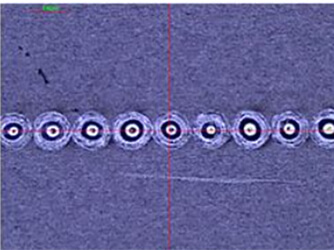

Pulse welding

Pulse welding spot superposition

| Welding mode | Pulse welding | Continuous welding |

|---|---|---|

| Penetration | Small | Big |

| Power consumption | Big | Small |

| Weld quality and appearance | Normal | Well |

Laser welding classified by laser welding method

According to the product combination, it is divided into the following:

Butt welding typically requires no gap or, if necessary, a gap of less than 0.05mm. The thinner the product being welded, the more stringent the requirements for the gap.

In the case of penetration welding, it is important to ensure a firm bond between the upper and lower layers. As the upper layer material becomes thinner, tighter fitting is required to achieve the desired result.

| Welding mode | Laser welding | Argon arc welding | Resistance welding | Brazing | Electron beam welding |

| Heat affected zone | Min | More | Commonly | More | Less |

| Thermal deformation | Less | More | Commonly | More | Less |

| Weld spot | Less | More | Commonly | More | Less |

| Weld quality and appearance | Well | Commonly | Commonly | Commonly | Preferably |

| Whether add solder | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Welding environment | No requirement | No requirement | No requirement | No requirement | Vacuum |

| Consumables | / | Welding wire or replacing tungsten electrode | Copper electrode | Solder | Faster |

| Welding speed | Faster | Slow | / | / | / |

| Degree of automation | High | Commonly | Commonly | Commonly | Commonly |

Pulse / continuous welding

| Difficulty | Stainless steel | Die steel | Carbon steel | Alloy steel | Nickel | Zinc | Aluminum | Gold | Silver | Copper |

| Stainless steel | easy | |||||||||

| Die steel | easy | easy | ||||||||

| Carbon steel | easy | easy | easy | |||||||

| Alloy steel | easy | easy | easy | easy | ||||||

| Nickel | easy | easy | easy | easy | easy | |||||

| Zinc | easy | easy | easy | easy | easy | easy | ||||

| Aluminum | hard | hard | hard | hard | slightly difficult | hard | easy | |||

| Gold | hard | hard | hard | hard | hard | hard | hard | slightly difficult | ||

| Silver | hard | hard | hard | hard | hard | hard | hard | hard | hard | |

| Copper | slightly difficult | hard | hard | hard | slightly difficult | hard | slightly difficult | hard | hard | easy |

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, with a carbon content ranging between 0.04% and 2.3%. To ensure the steel’s toughness and plasticity, the carbon content typically does not exceed 1.7%.

Alloy steel is produced by intentionally adding alloying elements, such as Mn, Si, Cr, Ni, Mo, W, V, Ti, etc., during the smelting process. These alloying elements can be used to improve the mechanical properties, process properties, or other special properties of the steel, such as corrosion resistance, heat resistance, and wear resistance.

Classification by chemical composition:

(1) Carbon steel:

a. Low carbon steel (C ≤ 0.25%);

b. Medium carbon steel (C ≤ 0.25 ~ 0.60%);

c. High carbon steel (C ≤ 0.60% ~ 2.11%).

The higher the carbon content, the easier it is to produce explosion holes in the molten pool.

(2) Alloy steel:

a. Low alloy steel (total alloy element content ≤ 5%);

b. Medium alloy steel (total alloy element content > 5 ~ 10%);

c. High alloy steel (total alloy element content > 10%).

The weldability of alloy steel depends on the alloy elements, and the weldability similar to the melting point characteristics of stainless steel is good.

(3) Stainless steel

Stainless steel refers to a type of steel that is resistant to weak corrosive media such as air, steam, water, and chemically corrosive media such as acid, alkali, and salt. It is divided into different types, including martensitic steel, ferritic steel, and austenitic steel.

Martensitic stainless steel is typically low-carbon or high-carbon steel with a chromium content ranging between 12% and 18%, and the main alloying elements are iron, chromium, and carbon. However, it has the worst weldability among all stainless steels. The welded joints are often hard and brittle, with a tendency for cold cracking. To reduce the likelihood of crack and embrittlement, preheating and tempering are recommended when welding stainless steel with a carbon content greater than 0.1%, such as 403, 410, 414, 416, 420, 440A, 440B, and 440C.

Austenitic stainless steel, on the other hand, refers to stainless steel with an austenitic structure at room temperature. This type of steel contains about 18% chromium and nickel, and has a stable austenite structure when the chromium content is between 8% and 10%, and the carbon content is about 0.1%. It generally has good laser welding performance. However, the addition of sulfur and selenium to improve its mechanical properties increases the tendency of solidification cracking.

Austenitic stainless steel has a lower thermal conductivity than carbon steel, with an absorption rate slightly higher than that of carbon steel. The welding penetration depth is only about 5-10% of that of ordinary carbon steel. Nevertheless, laser welding, which has a small heat input and high welding speed, is well-suited for welding Cr Ni series stainless steel. Some common austenitic stainless steel types include 201, 301, 302, 303, and 304.

Overall, stainless steel has good weldability, with a well-formed welding pool.

(4) 200 series – Cr Ni Mn

Austenitic stainless steel, 300 series – chromium-nickel

The meaning of each letter:

201 stainless steel contains manganese, which makes it prone to oxidation and rust in wet, salty, and poorly maintained environments (although it is still much better than iron products, and can be treated with wire drawing or polishing after oxidation and rust).

Unlike iron products, the surface electroplating layer cannot be treated after corrosion.

On the other hand, 304 stainless steel does not contain manganese, but has a higher chromium and nickel content, making it more resistant to oxidation and rust.

The price of 201 stainless steel is 3-4 times that of iron-based (chrome-plated or sprayed) furniture materials, while the price of 304 stainless steel is more than half or nearly twice that of 201 stainless steel.

The surface of 304 stainless steel is white with a metallic luster, similar to a plastic plate.

Ferritic stainless steel, with a body-centered cubic crystal structure, typically contains 11% – 30% chromium, and does not contain nickel (though it may contain small amounts of Mo, Ti, Nb, and other elements).

This type of steel has high thermal conductivity, low expansion coefficient, good oxidation resistance, and excellent stress corrosion resistance.

One example is 430 stainless steel.

Compared to austenitic and martensitic stainless steels, ferritic stainless steels have the least tendency to produce hot and cold cracks when laser-welded.

Welding of automobile steering system structure – continuous welding

Due to high surface reflectivity and high thermal conductivity, welding aluminum requires high power density, which makes it difficult to form a stable molten pool.

Many aluminum alloys contain volatile elements such as silicon and magnesium, leading to the formation of many pores in the weld.

The low viscosity and surface tension of liquid aluminum make it easy for the liquid metal in the molten pool to overflow, affecting the weld formation.

Some aluminum alloys may experience hot cracking during solidification, which is related to the cooling time and weld protection.

The higher the purity of aluminum, the better the welding quality.

Welding within the 3-Series aluminum is generally acceptable, while low-purity aluminum welding may produce explosion holes and cracks.

There are numerous process parameters that impact the quality of laser welding, including power density, beam characteristics, defocus, welding speed, laser pulse waveform, and auxiliary gas flow.

Power density is a critical parameter in laser welding.

A high power density can rapidly heat the metal to its melting point in microseconds, resulting in a high-quality weld.

The power density is determined by the peak power and the area of the solder joint.

Power density = peak power ÷ solder joint area

When welding highly reflective materials such as aluminum and copper, it is necessary to increase the power density. This can be achieved by using a higher current or power, and welding as close to the focal point as possible.

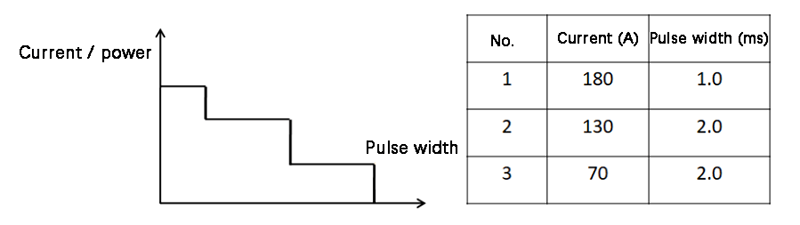

The laser pulse waveform is a critical factor in laser welding, particularly for sheet welding.

When the high-intensity laser beam interacts with the material surface, 60% to 90% of the laser energy is lost due to reflection, and the reflectivity changes with surface temperature.

The reflectivity of the metal changes significantly during a laser pulse.

When the metal is in a solid state, the laser’s reflectivity is high.

However, when the material surface melts, the reflectivity decreases, and the absorption increases, allowing for a gradual reduction in current or power.

Therefore, the pulse waveform is usually designed to accommodate these changes, such as:

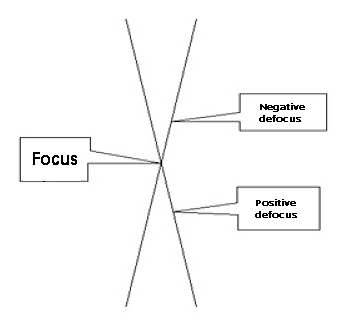

The term “defocus amount” refers to the deviation of the workpiece surface from the focal plane.

The position of the defocus directly impacts the keyhole effect during tailor welding.

There are two modes of defocusing: positive and negative.

If the focal plane is located above the workpiece, it is considered positive defocus, and if it is located below the workpiece, it is considered negative defocus.

When positive and negative defocuses are equal, the power density of the corresponding plane is roughly the same, but the shape of the molten pool is different.

Negative defocus can result in greater penetration, which is related to the formation of the molten pool.

Experimental results show that when the laser heating reaches 50 to 200 μS, the material starts to melt, forming liquid phase metal and partially vaporizing to form high-pressure steam. This results in a high-speed spray of dazzling white light.

At the same time, the high-concentration gas moves the liquid metal to the edge of the molten pool, creating a depression in the center of the pool.

During negative defocus, the internal power density of the material is higher than that of the surface, leading to stronger melting and gasification. This allows the light energy to be transmitted to the deeper part of the material.

Therefore, in practical applications, negative defocus should be used when deep penetration is required, and positive defocus should be used when welding thin materials.

Focus position:

The smallest spot with the highest energy can be achieved through spot welding. Conversely, when a small spot is required and the energy is low, spot welding can also be used.

Negative defocus position:

A slightly larger spot is appropriate for deep penetration continuous welding and deep penetration spot welding. As the distance from the focus increases, the spot size becomes larger.

Positive defocus position:

A slightly larger spot is suitable for continuous welding of surface seal welding or situations where low penetration is needed. As the distance from the focus increases, the size of the spot also increases.

The quality of the welding surface, penetration, heat-affected zone, and other factors are determined by the welding speed.

Penetration can be improved by either reducing the welding speed or increasing the welding current.

Reducing the welding speed is commonly used to improve penetration and increase the lifespan of the equipment.

Auxiliary blowing is a crucial process in high-power laser welding.

Firstly, it helps prevent metal sputtering from contaminating the focusing mirror by using coaxial protective gas.

Secondly, it prevents the buildup of high-temperature plasma generated during the welding process and stops the laser from reaching the material surface through sideblowing.

Thirdly, it uses protective gas to isolate the air and protect the welding pool from oxidation.

The choice of auxiliary gas and the volume of blowing air greatly influence the welding results, and different blowing methods can also have a significant impact on the welding quality.

For example, if the optical fiber diameter is 0.6mm and the focusing focal length is 120mm with a collimating focusing of 150mm, the focus diameter can be calculated as follows:

Focus diameter = 0.6 x 120/150 = 0.48mm

The specific configuration is determined based on the material, thickness, penetration, and fit clearance of the product.

Features of Long Focus: