Ever wondered how stainless steel can be both strong and resistant to corrosion? This article unravels the mystery behind PH stainless steel, a material that benefits from precipitation hardening. You’ll learn how its unique heat treatment process provides superior strength and durability compared to traditional stainless steel. Discover the types of PH stainless steel, their specific applications, and how they can significantly enhance your engineering projects. Get ready to explore the fascinating world of advanced metallurgy and its practical implications for modern manufacturing.

Excellent question.

Compared to traditional martensitic types, PH types offer advantages such as high strength, excellent corrosion resistance, and simplified heat treatment processes.

PH stands for “precipitation hardening,” a type of heat treatment that differs slightly from the traditional heat treatment of martensitic types.

An initial “solution treatment” is conducted at high temperatures, typically at 1900 degrees Fahrenheit, to ensure that all alloy elements needed for the hardening reaction are evenly distributed in the metal structure.

At these temperatures, the structure is austenitic. Starting from this temperature, the alloy cools at a rate that maintains the distribution of hardening elements in solution.

Based on the chemical composition of specific alloys, the structures produced after “solution treating” are martensite, semi-austenite, or austenite.

These structures contain more hardening elements than fully stable ones, so they are merely waiting for additional heat treatment to induce changes within.

However, they are stable enough that we can choose to manufacture components before the final hardening heat treatment.

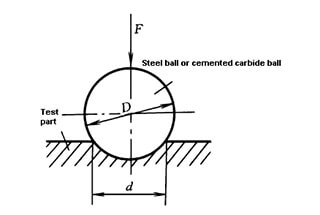

This additional, relatively low-temperature heat treatment is referred to as “aging”. The increased temperature and time allow element mobility to combine and form “precipitates” (think particles), which subsequently strengthen the structure.

Let’s categorize the types of PH alloys based on the structure achieved through solution treatment…

They form low-carbon martensite, which is relatively softer but also brittle, during solution treatment. The alloy should not be used under solution treatment conditions.

When reheated to aging temperature, the formed particles further strengthen the structure and enhance toughness and corrosion performance.

The resultant heat treatment condition is represented by the letter H followed by the aging temperature.

For example: H900 indicates that it has undergone solution treatment, followed by aging at 900 degrees Fahrenheit. Through a second simple heat treatment, hardness increases, and the minimum yield strength reaches 170,000 psi.

Condition ranges from H900 to H1150, or even double H1150 (aged twice at 1150 degrees Fahrenheit). The higher the aging temperature, the lower the strength, but the toughness increases.

H1150M is the aging condition that produces the lowest hardness.

Solution treated, solution annealed, annealed, and Cond A are synonyms when describing conditions.

Typically, these types undergo solution treatment at the steel mill, followed by aging treatment after additional parts manufacture.

If it is already in the desired aging state, no further heat treatment is needed. This entirely depends on the content of the optimum manufacturing plan provided.

Common stainless steels in this group include 17-4 (also known as 630), 15-5, 13-8, 450, and 455.

The chemical composition of these alloys results in a range of distinct structures during heat treatment steps.

Like all PH stainless steels, the first step is “solution treatment”. This achieves a uniform distribution of elements involved in the hardening reaction within the austenitic structure.

After cooling from the solution temperature, the structure of these alloys remains in the austenitic state at room temperature… but only temporarily.

This relatively soft and ductile austenitic structure gives us the opportunity to perform a wider range of manufacturing than martensitic types allow before hardening.

Well… it seems we’ve found a way to have our cake and eat it too. We can achieve softer, more formable metal at this stage, and then we can harden it to the high strength of fully martensitic PH stainless steel.

To achieve the final hardening of the material, we first need to enable the austenitic structure to transform into the martensitic structure. There are three methods to form martensitic structure.

Any one of:

Cooling to around -100 degrees Fahrenheit and holding for up to 8 hours.

Or

Heating to about 1400 degrees Fahrenheit and holding for up to 3 hours.

Or

Cold working (like cold rolling plate)

Now that we have the martensitic structure, the familiar aging treatment can perform the final hardening in these types.

The two-step hardening process for these grades is indicated by a prefix followed by H and the aging temperature. The prefix indicates the method of forming martensite.

For instance:

Common examples of semi-austenitic steel grades include 17-7 (AISI 631), 15-7 (632), AM-350 (633), and AM-355 (634).

Applications typically demand the superior cleanliness of remelted steel, with the precise details of the required heat treatment varying with the steel grade and specification.

The last category of PH stainless steels are those that retain an austenitic structure from the solution treatment to the aging process.

Although their strength is much lower than the other two PH types, they are non-magnetic and have a strength higher than 300 series stainless steels.

Solution treatment typically occurs at higher temperatures compared to other types. Aging also takes place at higher temperatures, usually above 1300.

In most cases, only one aging treatment is applicable to the alloy. As the aging temperatures are higher, these alloys can be used at temperatures where other PH types would lose strength.

An example of this type is A286 stainless steel, which has a superior vacuum remelt cleanliness ideal for aerospace engine or turbine applications.