Have you ever wondered how metal sheets are precisely shaped into various forms? Press braking is a fascinating process that does just that. By applying force to a sheet of metal over a die, it bends and molds the material into desired shapes. This article explores different methods of press braking, such as air bending and coining, detailing their applications and benefits. You’ll learn about the nuances of each technique and understand why press braking is essential in metal fabrication. Dive in to discover the intricate art of transforming metal with precision.

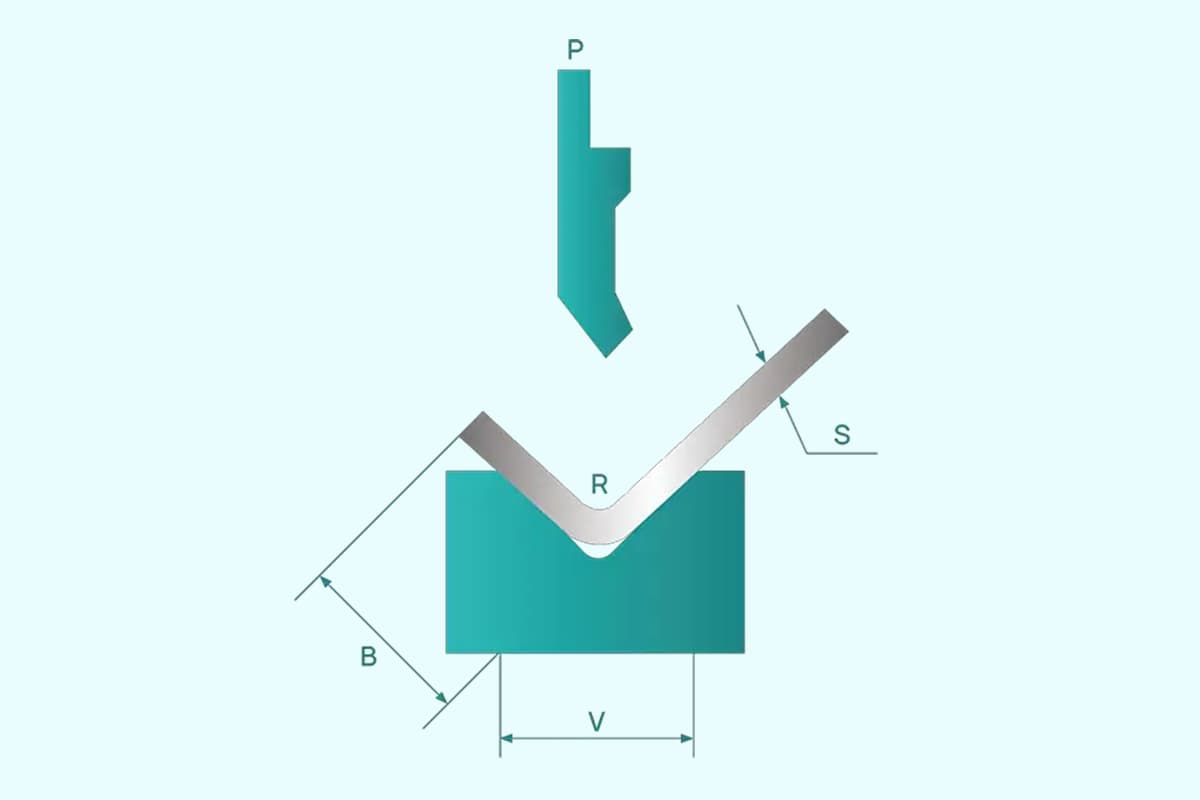

Press braking is the mechanical process of deforming sheet material supported over a female (“V” shape) die by applying force through the punch.

Permanent deformation of the sheet part occurs along the line of contact when the force exceeds the yield strength of the material.

There are two methods for generating the force required to bend the sheet material:

Related reading: What Is a Press Brake?

After cutting, press braking is one of the easiest operations carried out with sheet metal and basically it involves the cold plastic deformation of the sheet metal.

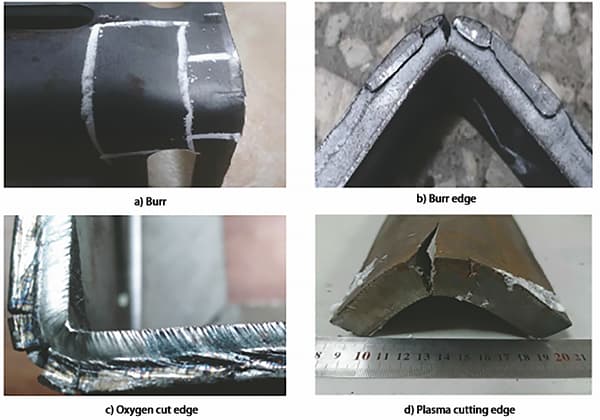

An essential requirement for bending is the material’s bendability, that is, its ability to be bent without cracking or breaking. This property requires good malleability and elongation, purity and low hardness. Mild steel with a low percentage of carbon (< 0.2%) and low alloy steel (none of the added elements reaching 5%) have good bendability.

Thanks to the wide range of standard press brake tools and very quick machine setup, press braking offers the potential to obtain products with different features to meet different needs.

This is in contrast to deep drawing (e.g. of car components), which enables the production of an unlimited range of irregular shapes, but requires a great deal of time and high costs to design and produce the necessary mold with no possibility of modifying the results.

Deep drawing is therefore convenient for high-quantity production, whereas press braking enjoys a much broader use.

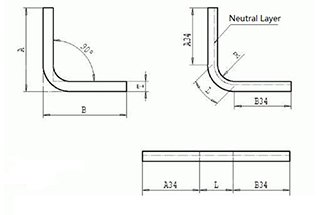

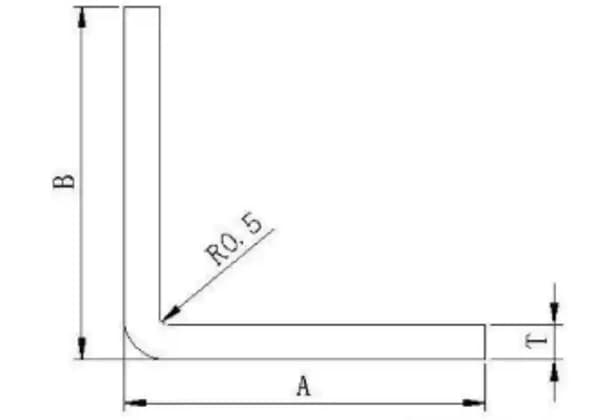

Press braking is carried out by laying a sheet of metal between an upper and a lower tool (punch and die respectively); the punch is lowered towards the die and pushes the sheet metal into it causing its permanent plastic deformation.

With press braking it is possible to obtain quite complicated pro-files by making bends in the correct sequence. Sheet metal is usually moved and positioned by hand.

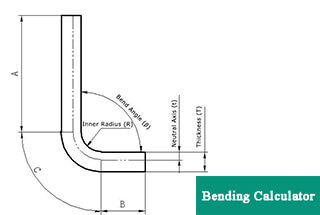

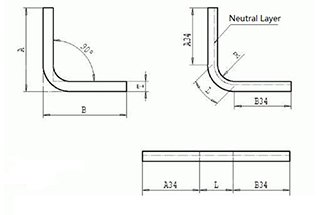

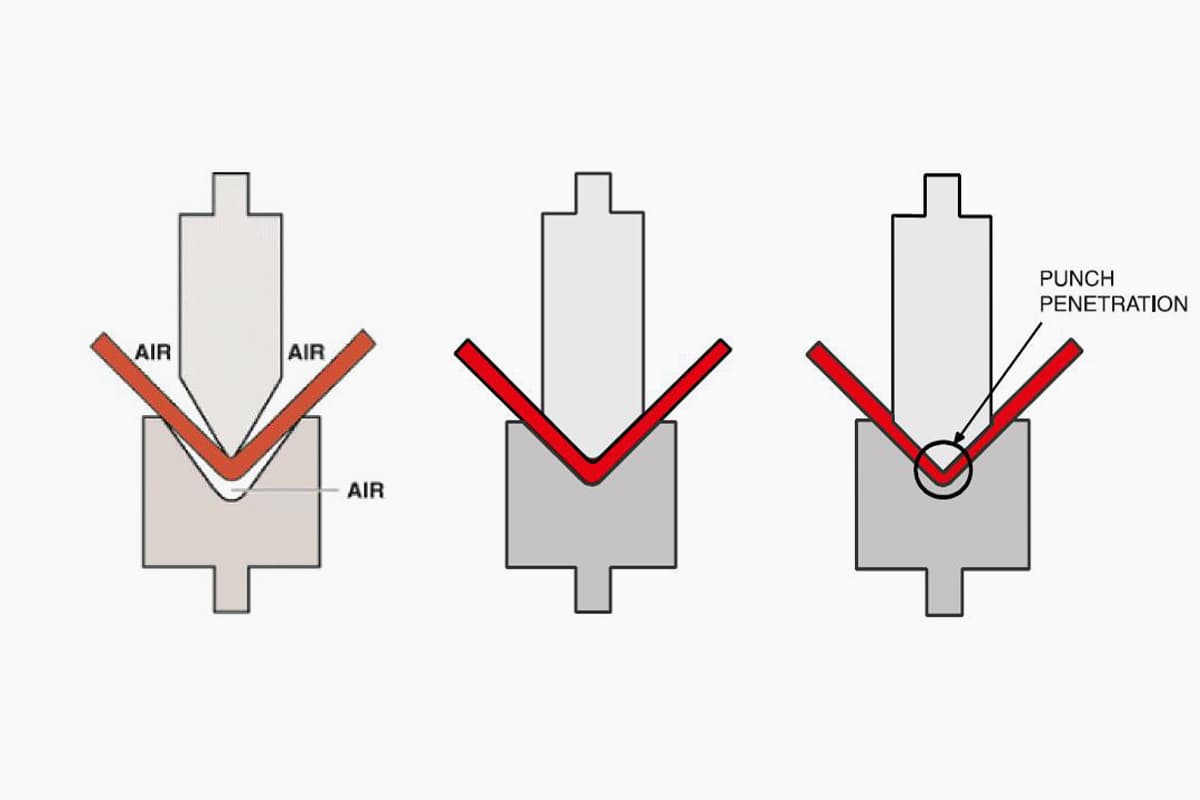

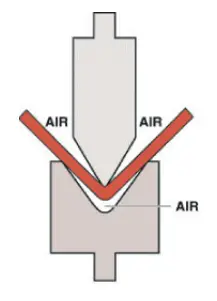

With air bending, the sheet is deformed in a three point contact between the punch and rounded shoulders of the die. The sheet material does not make contact with the sides of the die or the punch.

Note:

When the applied force is released, a partial springback occurs, due to the elastic properties of the material.

Typical air bending dies are configured with an included angle of 85 degrees so that the part can be over bent, with resulting springback to the desired 90 degrees.

With air bending, the operator can form parts with different bend angles using the same die set for a given material thickness. This is achieved by controlling the punch penetration into the work piece over the die.

Acute dies with an included angle of 60 degrees can be used to air bend sheet metal gauge parts for included angles greater than 60 degrees. The angle of the formed part is determined by the depth of the punch penetration into the die.

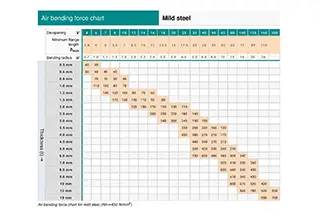

Tonnage requirements for air bending are typically published for mild steel of specified tensile strength, material thickness and die opening configuration. See Figure 2.2-1.

With bottom bending, the punch applies sufficient tonnage so that the sheet material conforms to the geometry of the die set. With this method the formed part should experience little or no springback.

The die included angle is normally 90 degrees.

Typical tonnage requirements for bottom bending are up to four times greater than for air bending.

Although variances in the formed part angle are lessened with bottom bending, the die set is limited to a single angle part forming operation.

With coining, the punch applies sufficient tonnage so that the sheet material conforms to the geometry of the die set and experiences a slight degree of thinning at the point of contact. With this method the formed part should experience no springback.

The die included angle is normally 90 degrees.

Typical tonnage requirements for coining are four to eight times greater than for air bending – a disadvantage due to costs associated with higher capacity press brakes and maintenance of equipment and tooling.

Although variances in the formed part angle are lessened with coining, the die set is limited to a single angle part forming operation.